Tumba Madžari Goddess: What if your home could watch over you? What if the very walls held a spirit of protection, a maternal presence woven into the clay and timber? Forget everything you know about ancient Venus figurines. This is not a simple fertility idol.

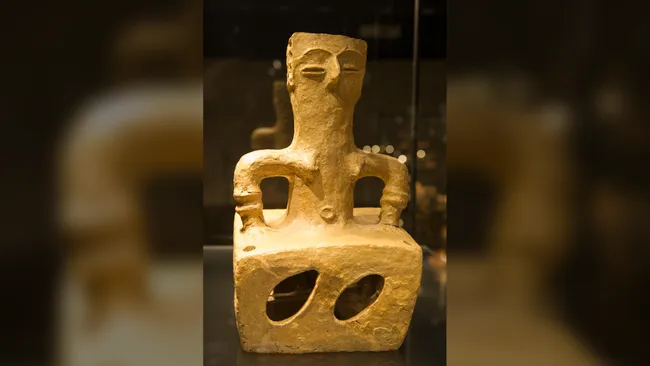

In the heart of the Balkans, archaeologists unearthed a silent sentinel from a forgotten era. She is the Tumba Madžari Great Mother. Crafted 7,800 years ago, her design is a revolutionary mystery. Her lower body is a perfect, hollow cube.

This is no artistic whim. This boxy goddess was the spiritual blueprint of the Neolithic house. She was designed not just to stand in a home, but to become it. She reveals a mind-blowing fusion of architecture, divinity, and family that rewrites our understanding of Europe’s first farmers.

The Astonishing Find: A Domestic Cathedral

The discovery site, Tumba Madžari, sits near modern Skopje, North Macedonia. It is a key to the Neolithic world. Excavations revealed a vibrant village from 5800–5200 BC. This was the dawn of settled life.

Archaeologists uncovered the foundations of distinctive homes. These were not mere huts. They were substantial structures built with wooden posts, woven branches, and thick clay plaster. They were the center of universe for their inhabitants.

In 1981, within one such house, a find of profound importance came to light. Near the central hearth—the literal and symbolic heart of the home—they found her. The Great Mother figurine lay amidst dozens of intact pots and vessels. This was no discarded object.

She had been placed with purpose. The artifacts surrounding her were domestic treasures. This context was the first clue. She was not hidden in a shrine or grave. She was in her place. She was an active, integrated member of the household.

Decoding the Boxy Goddess: Architecture as Divinity

The Great Mother’s form is her most electrifying feature. Standing 15.4 inches tall, she commands attention. Her upper body is human, with pronounced breasts, a navel, and arms resting on her cubic lower half. Her face, with linear eyes under arched brows, holds a serene, watchful power.

But the cube changes everything. This geometric base is a direct, intentional mimicry of the square Neolithic houses of Tumba Madžari. The symbolism is stunningly clear. The goddess does not merely occupy the house. She embodies it. She rises from its very foundation.

Her hollow interior suggests a breathtaking function. Experts theorize she was a living altar. Families could place smoldering incense, grains, or herbs within her. Smoke would curl from her body, a sacred offering merging with the home’s own hearth smoke.

This design is a rare masterpiece of Neolithic thought. It symbolizes total protection. The goddess was the guardian of the roof, the walls, the stored food, and the family within. Her boxy form was a constant, tangible reminder: the home itself was sacred because it was an extension of the Mother.

Global Significance: A Balkan Singularity

Mother goddess figurines are found across Neolithic Europe and the Near East. They speak to a widespread reverence for fertility and creation. Yet, the Tumba Madžari Great Mother stands apart. She is a regional icon of breathtaking specificity.

This unique “house-form” design is found only in the Balkan Neolithic. It represents a localized theological explosion. Here, the concept of the Great Mother evolved beyond a general earth deity. She became deeply, personally domestic.

This artifact shatters the notion of a monolithic “Stone Age religion.” It shows how ancient spiritual ideas were brilliantly adapted to local life. For the farmers of Tumba Madžari, security and survival depended on a sturdy home and a fruitful land. Their goddess perfectly fused these two needs into one powerful, protectress form.

She represents a forgotten era of hyper-localized belief. A time when the divine was not in a distant temple, but in the clay under your feet and the walls at your back. Her discovery forces a global reassessment of how early societies visualized the forces that guarded their daily lives.

The Cult of the Great Mother: More Than Fertility

The Archaeological Museum of North Macedonia, where she now resides, states her role clearly. The woman as child-bearer was equated with a fertility cult. But the Tumba Madžari figure implies a doctrine far richer.

This was likely a cult of the hearth, the harvest, and lineage. By placing her near the oven and stored pots, the inhabitants linked her to food preparation, preservation, and family continuity. She watched over the rituals of daily life.

Her braided hair and traces of brown paint hint at careful adornment. She was likely dressed, painted, and involved in seasonal household rituals. She was a fixed point in their world. A spiritual anchor in a life subject to the unpredictability of nature.

This figurine is a direct window into the Neolithic mind. It reveals a worldview where the domestic and the divine were inseparable. The safety of the house and the fertility of the family were two sides of the same clay coin.

What This Means for History: Rethinking the Neolithic Home

The Tumba Madžari Great Mother forces historians to redefine the “home” in prehistoric societies. It was not just a shelter. It was a microcosm of the universe. A charged space where architecture and belief merged.

This find illuminates the profound psychological world of Europe’s first farmers. They invested their dwellings with a guardian spirit. This practice speaks to their anxieties, hopes, and profound connection to their constructed environment.

Furthermore, she highlights the incredible artistic and symbolic sophistication of the Balkan Neolithic. This was not crude art. It was a highly conceptual, architecturally-informed sculpture. It represents a peak of symbolic thinking that rivaled contemporaneous cultures in Mesopotamia and Anatolia.

Her legacy is a reminder. The deepest human needs—for protection, nurture, and meaning—have always found form in art. The Great Mother is one of humanity’s most powerful and enduring answers to those needs. She was the spirit of the house, made tangible to hold, to see, and to trust.

In-Depth FAQs

1. How was the Tumba Madžari site discovered?

The site was identified through archaeological surveys in the region surrounding Skopje. Systematic excavations began in the late 20th century, revealing the extensive remains of a Neolithic settlement. The “Great Mother” figurine was unearthed in 1981 during these professional excavations, found in situ within the remains of a house.

2. Why is the cube shape so significant?

The cube is a direct, intentional representation of the square house plans found at Tumba Madžari and across the Balkan Neolithic. This unique design is a profound piece of symbolic art. It physically merges the goddess with the architecture she protects, suggesting a belief system where the home itself was a sacred, living entity under her guardianship.

3. How do we know it was meant for protection?

The contextual evidence is key. She was found placed centrally in a house, near the hearth and domestic tools—the core of family life. Her imposing, watchful posture and her form becoming the house strongly imply a guardian role. This aligns with broader Neolithic beliefs where figurines were often used as protective talismans for the home, harvest, and family.

4. Is this the only “house-form” goddess found?

While other mother goddess figurines are common, this specific architectural design—where the lower body forms a cube or house—is a distinct cultural feature of the Balkan Neolithic period. Similar, though not identical, concepts have been found at related sites in the region, making the Tumba Madžari figure the most iconic and complete example.

5. What does this tell us about the status of women in Neolithic society?

The figurine is a powerful symbol, but it should be interpreted carefully. It reflects the ideological and possibly religious importance of motherhood, fertility, and the domestic sphere. It suggests these concepts were central to community identity and survival. However, it does not directly translate to the social or political power of individual women, which is harder to ascertain from archaeology alone. It shows what the society venerated, not necessarily how it was governed.