1900-Year-Old Roman Vial: For centuries, scholars have read the works of Galen of Pergamon—the towering figure of Roman medicine—with a mix of awe and queasiness. His texts describe complex recipes for ailments, some containing a shocking ingredient: human feces. Was this just theoretical shock value, or desperate folklore? Or was it a calculated, if revolting, medical practice? The written word left room for doubt.

Now, cutting-edge forensic science has removed all doubt. In a sealed, 1,800-year-old Roman perfume bottle, buried with its owner in the very city where Galen practiced, researchers have found the definitive, biochemical signature of a feces-based remedy. This isn’t a reinterpretation of a text. It is material proof of ancient pharmaceutical reality, confirming that some of history’s most sophisticated doctors deliberately prescribed what we consider the ultimate waste product as medicine. The “why” opens a stunning window into the pragmatic, microbial-blind world of ancient healing.

The Astonishing Find: A Biochemical Autopsy of a Cure

The discovery is a masterpiece of interdisciplinary sleuthing, blending archaeology, chemistry, and medical history.

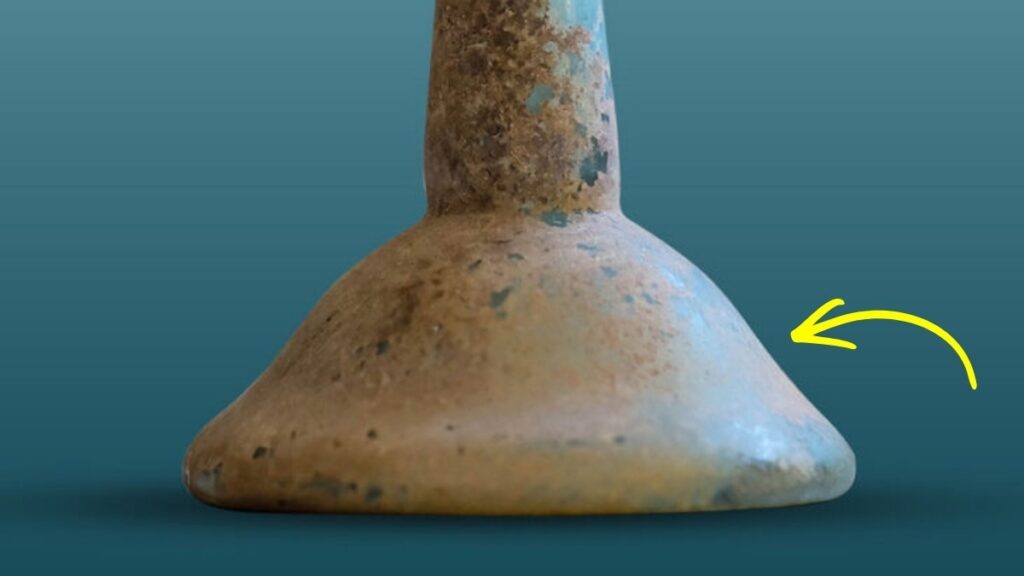

The Time Capsule VialThe key artifact is a small unguentarium—a glass vial for oils or unguents—recovered from a tomb in Pergamon (modern Bergama, Turkey). Its intact seal was the miracle. For 18 centuries, it preserved not just its contents, but the precise biochemical profile of its recipe, uncontaminated by the outside world.

The Forensic BreakdownUsing gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, a technique that identifies individual molecules, the team performed a molecular autopsy on the brownish residue. The results were unambiguous:

- Coprostanol & 24-Ethylcoprostanol: These are sterols, stable organic compounds that form when cholesterol is metabolized in the gut. Their presence is a definitive biomarker for mammalian feces.

- The Human Signature: The specific ratio of these two compounds pointed to a human source. This was not animal dung.

- The Masking Agent: Traces of thyme were also identified—a clear attempt to counteract the smell, making the medicine palatable for the patient.

Deep Dive: Galen’s Gross Logic

To modern sensibilities, this is horrifying. But in the framework of Galenic medicine, it was rational, even sophisticated.

The Principle of “Similars” and AntiquityGalen’s system was built on humoral theory, but it also incorporated ancient concepts of sympathetic magic and the therapeutic use of “loathsome” materials. Feces, as a waste product, was thought to contain the expelled “virtue” or essence of the body’s digestive power. Its use followed a principle where a repulsive, potent substance could drive out disease.

A Probiotic in Disguise?While the Romans had no concept of microbes, modern science offers a startling hypothesis. Human feces contains a complex microbiome. In cases of severe intestinal infection (like Clostridioides difficile), a modern treatment is Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)—introducing healthy donor feces to repopulate the gut. Is it possible that ancient Roman physicians, through pure empirical observation, stumbled upon a proto-biotic therapy that actually worked for certain gut disorders? The addition of antimicrobial thyme might have been an attempt to control (unknowingly) dangerous pathogens.

The Social Ritual of MedicineThe addition of thyme, wine, or vinegar wasn’t just practical. It transformed a foul substance into a ritualized, professionally prepared concoction. The patient wasn’t just eating waste; they were consuming a pharmakon—a prepared drug from a respected physician. This packaging was crucial for compliance and the placebo effect, which Galen himself understood profoundly.

Global Implications: Bridging Text and Material Reality

This discovery is a landmark for the history of science and medicine.

Validating the Historical RecordIt proves that the most extreme recipes in ancient medical texts were actually compounded and used. This moves the study of historical medicine from literary analysis into the realm of experimental archaeology and material science. We can now test other alleged remedies against physical evidence.

The Democratization of “Yuck”Fecal medicine wasn’t a Roman oddity. Similar remedies appear in ancient Egyptian, Chinese, and Medieval European pharmacopoeias. This find provides a chemical methodology to investigate these claims globally. It forces us to confront the universality of using bodily products in healing, challenging our linear narrative of medical progress.

A New Chapter in Archaeological ChemistryThe study pioneers the use of specific sterol biomarkers for identifying organic residues in archaeological contexts. This technique can now be applied to cooking pots, storage jars, and other vessels to detect differences in diet, ritual offerings, and yes, more medical preparations, revolutionizing our understanding of ancient daily life.

What This Means for History: A More Complex, More Human Past

The Pergamon vial shatters simplistic views of the past as either gloriously advanced or hopelessly primitive. It reveals a medical culture that was both highly systematic and willing to embrace the transgressive.

It shows Galen and his peers not as superstitious quacks, but as relentless empiricists working within their paradigm, trying everything in their arsenal to alleviate suffering—even if that meant bottling up the unthinkable. Their “success” likely relied on a complex cocktail of placebo effect, occasional genuine microbiological action, and the inherent resilience of the human body.

This small glass bottle, once holding a remedy that would make us gag, ultimately contains a profound truth: the history of medicine is a history of human desperation, ingenuity, and the enduring, often messy, quest to heal.

5 In-Depth FAQs

1. How can we be sure the feces was medicinal and not just something else?The context is critical. The substance was found in a sealed, purpose-made glass pharmaceutical vial (an unguentarium) in a tomb, placed as a grave good. This strongly indicates it was a valued personal possession, likely for health in the afterlife. Combined with the textual records of Galen explicitly describing such preparations, the evidence for intentional medicinal use is overwhelming.

2. What specific ailments would this “treatment” have been used for?According to Galen’s texts, fecal preparations (often referred to as “sterconaceous” medicines) were prescribed for a range of issues: severe intestinal inflammation and infection, stubborn wounds, and surprisingly, reproductive and gynecological disorders. The logic may have been to apply a substance of “expulsive” power to drive out disease or imbalance.

3. Isn’t this incredibly dangerous? What about parasites and diseases?By modern standards, it was extremely high-risk. Without knowledge of pathogens like hepatitis, E. coli, or parasites, the practice could easily transmit deadly diseases. The addition of thyme (antimicrobial) or wine/vinegar (acidic) might have reduced some risk unknowingly, but the danger was profound. This highlights the terrible calculus of ancient medicine: the disease might kill you, but the cure also could.

4. Why is Pergamon such a significant location for this find?Pergamon was a major center of healing, home to the Asclepieion, a sanctuary dedicated to the god of medicine, Asclepius. It was also the hometown and workplace of Galen, the most influential physician of the Roman Empire. Finding this vial there directly links the physical artifact to the most advanced medical theoretical system of the time, making it the equivalent of finding Newton’s own prism or Einstein’s original chalkboard.

5. What does this discovery mean for the study of other ancient medicines?It sets a powerful precedent. It proves that residue analysis can test the reality behind historical texts. Scholars can now re-examine other ancient medicinal recipes—for opium, henbane, silphium, or mercury—and search for surviving samples in sealed containers. It moves the field from “they wrote about it” to “we have chemically confirmed they used it,” enabling a truer, materially-grounded history of global pharmacology.