For over two millennia, the priests Nes-Min and Nes-Hor lay in sacred stillness, their stories sealed within linen and resin. We knew their names, their titles, the era they served the gods. But of their lives—their pains, their daily struggles, the intimate objects they chose for eternity—we knew nothing. Their bodies were time capsules, but we lacked the key.

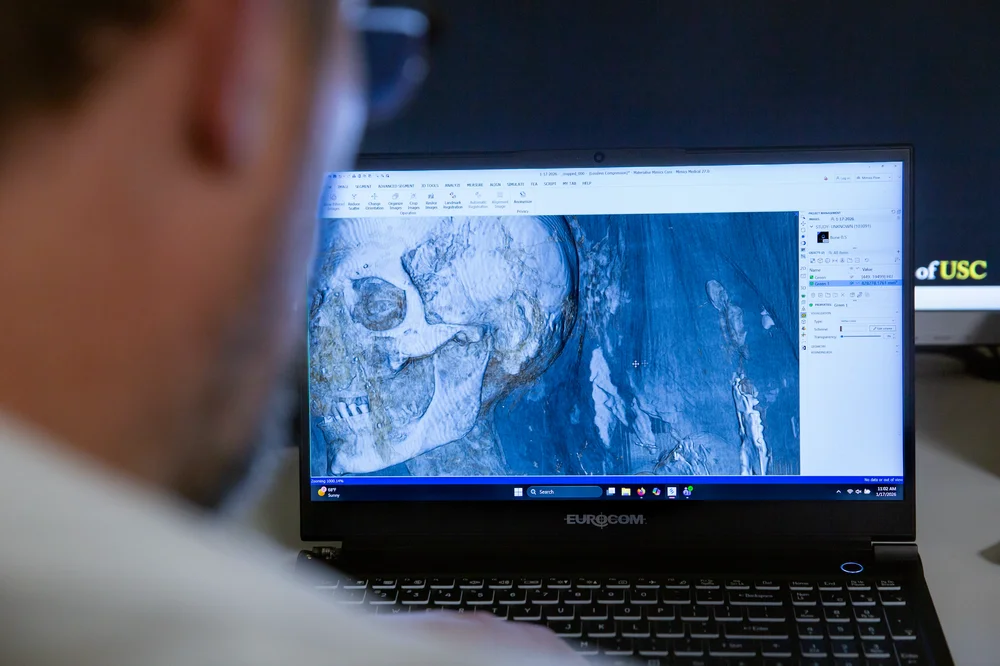

That key is now a state-of-the-art 320-slice CT scanner. In a revolutionary non-invasive “digital autopsy,” radiologists have performed the most detailed forensic examination of these ancient individuals to date, peeling back the wrappings without touching a single thread. The result is not just data; it’s a profound re-humanization. We are no longer looking at “mummies,” but at men who suffered chronic back pain, endured toothaches, and walked with a limp. We are meeting them, for the first time, in recognisable detail—down to the curve of an eyelid and the beads of their burial nets.

The Astonishing Procedure: A Digital Unwrapping

The methodology itself is a breakthrough in ethical archaeology. The mummies, each weighing 200 pounds within their sarcophagus halves, were scanned intact. This preserved their integrity while granting unprecedented access.

The Visual VaultThe high-resolution scans acted like a super-powered X-ray, generating hundreds of cross-sectional slices. These were then computationally stitched together to create hyper-detailed 3D digital models. This allowed researchers to:

- Visualize soft tissues like shrunken eyelids and lips.

- Map the entire skeletal structure with precision.

- Identify and digitally extract small burial artifacts nestled within the layers.

From Data to Physical RealityThe team then performed a kind of technological resurrection. Using medical-grade 3D printers, they produced full-scale, tangible replicas of the priests’ skulls, spines, and damaged hip joints. They could even print the hidden scarab beetles. This transforms abstract imaging data into objects that can be held, studied, and understood in a visceral way by researchers and the public alike.

Deep Dive: The Patients’ Charts from 300 BC

The scans provided starkly intimate medical biographies, bridging 2,300 years of human experience.

Nes-Min: The Elder with a Bad BackLiving around 330 BCE, Nes-Min’s spine told a story of a long life. The CT revealed a collapsed lumbar vertebra, a classic sign of degenerative disc disease exacerbated by age and likely the physical demands of priestly ritual. He likely lived with persistent, nagging lower back pain—an ailment as common in ancient Thebes as in modern offices.

Nes-Hor: The Younger Man Who Lived Longer, in PainDespite being identified as chronologically younger (c. 190 BCE), bone analysis suggested Nes-Hor lived longer. His quality of life, however, may have been severely compromised. The scans revealed:

- Extensive tooth decay and abscesses, indicating a painful dental condition.

- Severe deterioration of one hip joint, consistent with advanced osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis. This would have caused a pronounced limp and significant, debilitating pain with every step.

Their ailments—degenerative joint disease, dental pathology—are mirror images of modern outpatient clinic complaints, shattering the illusion that ancient lives were categorically different from our own.

The Hidden Votive Cache: Amulets for the Journey

Beyond anatomy, the technology illuminated spiritual practice. Nestled within Nes-Min’s wrappings, the scanner pinpointed small, shaped amulets:

- Scarab Beetles: Symbolizing rebirth, transformation, and the sun god Khepri.

- A Fish: Likely representing abundance, fertility, or protection (like the tilapia fish, associated with rebirth).

These weren’t merely placed in the coffin; they were integrated into the mummy’s sacred microcosm, positioned to actively protect and empower Nes-Min in the Duat (the afterlife). We can now know their exact placement and size without ever disturbing the sacred bundle.

Global Implications: A New Ethical Standard for Bioarchaeology

This project is a paradigm shift for how we interact with human remains across cultures.

The Non-Invasive ImperativeThe technique sets a new gold standard for ethical study. It maximizes information gain while minimizing physical intrusion and destruction. This is crucial for respecting the cultural and spiritual significance of remains, especially for descendant communities and sensitive collections worldwide.

Democratizing the InaccessibleThe 3D-printed replicas solve a major museological dilemma. Curators can now allow researchers and the public to “handle” exact copies of fragile remains, enabling tactile study and engagement without risking the priceless originals. The data can be shared globally with scholars who cannot travel to the collection.

Bridging Clinical and Historical MedicineThe collaboration between radiologists and archaeologists creates a powerful new field: paleo-radiology. Clinical expertise in reading modern pathologies is directly applied to ancient bodies, yielding more accurate diagnoses and a deeper understanding of the history of disease, pain, and human resilience.

What This Means for History: Intimacy Recovered

The story of Nes-Min and Nes-Hor is no longer about the ritual of mummification. It is about the human experience that preceded it. The technology has restored their individuality.

We see them not as icons of a death cult, but as individuals who carried physical burdens while performing their sacred duties. The collapsed vertebra and the arthritic hip are not just pathologies; they are biographies written in bone, testaments to lifetimes of movement, strain, and adaptation.

This project proves that the future of understanding the past lies in such sophisticated, respectful looks beneath the surface. It allows these ancient priests to fulfill, in a way, their deepest wish: to be known and remembered, not just as names on a cartonnage, but as men who lived, worked, suffered, and were prepared for eternity with care and sacred beads nestled close to their skin.

5 In-Depth FAQs

1. How does a 320-slice CT scanner differ from a standard hospital CT?A standard CT scanner might have 16-64 detector rows (slices). A 320-slice scanner is a top-tier volumetric CT that can capture a significantly larger volume of the body—in this case, nearly the entire mummy—in a single rotation. This results in higher resolution, faster scan times (reducing motion artifact), and the ability to create exquisitely detailed 3D models, especially of complex bony structures like the spine and skull.

2. Why is bone analysis a better indicator of age-at-death than historical era for Nes-Hor?Historical dating (c. 190 BCE) comes from contextual clues like coffin style or inscriptions. Osteological age is determined by examining skeletal markers of senescence, such as:

- Cranial suture closure.

- Pubic symphysis and rib end morphology.

- Degenerative changes (osteophytes, joint wear).Nes-Hor’s bones showed advanced degenerative signs, suggesting his biological age was greater than the “younger” historical period might imply. He lived a long life, well into his older years.

3. What can the specific hip damage in Nes-Hor tell us about his life?Severe unilateral (one-sided) hip degeneration suggests a lifetime of asymmetrical weight-bearing. This could result from a congenital condition, an old injury that never healed properly, or a occupational habit (like consistently standing or leaning in one posture during long rituals). The pain would have been chronic and likely shaped his mobility and daily activities profoundly.

4. How does finding amulets within the wrappings change our understanding of burial practice?It emphasizes the mummy as an integrated ritual object. Amulets weren’t just grave goods placed around the body; they were actively incorporated into the sacred corporeal package. Their placement against the skin or within specific layers of linen was ritually prescribed in texts like the Book of the Dead to provide targeted protection for specific organs or spiritual functions during the perilous journey to the afterlife.

5. What is the long-term scientific value of the 3D digital models?The digital files are a permanent, shareable record. They allow for:

- Future re-analysis as diagnostic software improves.

- Virtual dissection to test hypotheses about organ placement or wrapping techniques.

- Metric analysis (precise measurements of bones, artifacts) without handling the mummy.

- Global collaboration, as the dataset can be sent to any specialist in the world for a second opinion or specialized study, democratizing access to these irreplaceable remains.