Forget everything you know about silent, static ruins. Imagine, instead, the deafening sound of history. The clamor of hammers shaping stone amulets. The splash of thousands of fish being processed in vast vats. The quiet sobs for children laid to rest in giant wine jars.

This is not a single moment frozen in time. This is centuries of vibrant, beating life—and death—suddenly screaming back into existence.

Archaeologists have just pulled back the sand from a revolutionary site in Egypt’s western Nile Delta. At Kom Al-Ahmar and Kom Wasit, they didn’t find just another tomb or a solitary temple. They uncovered an entire forgotten economic engine. A place where industry and eternity lay side-by-side.

This is the story of a community that thrived in the shadow of Alexandria. A hub that connected the deep roots of Pharaonic Egypt to the vast networks of the Roman Mediterranean. What they made here, and how they buried their dead, is rewriting our understanding of daily life in one of the ancient world’s most dynamic crossroads.

The Astonishing Find: More Than Just Tombs

The initial announcement hinted at a “Roman-era necropolis.” But the reality is far more complex, and infinitely more fascinating. This is a multi-layered time capsule.

The joint Egyptian-Italian mission, a brilliant collaboration between the Supreme Council of Antiquities and the University of Padua, has revealed two intertwined worlds. First, a sprawling complex of ancient industrial workshops. Second, a neighboring city of the dead that served its people.

This isn’t a lucky stumble. It’s the result of strategic, scientific excavation. The team pieced together ancient settlement patterns, leading them to this specific patch of Beheira governorate. What they found surpassed all expectations.

The Delta’s Industrial Powerhouse

Walk into the large, multi-roomed structure they uncovered. You are not entering a palace or a home. You are stepping onto the factory floor of antiquity.

Follow the smell of the sea. Two rooms were dedicated entirely to large-scale fish processing. The evidence? A mind-blowing 9,700 fish bones. This was no small family operation. This was industrial-scale production of salted fish, or garum, a prized fermented sauce beloved across the Roman Empire.

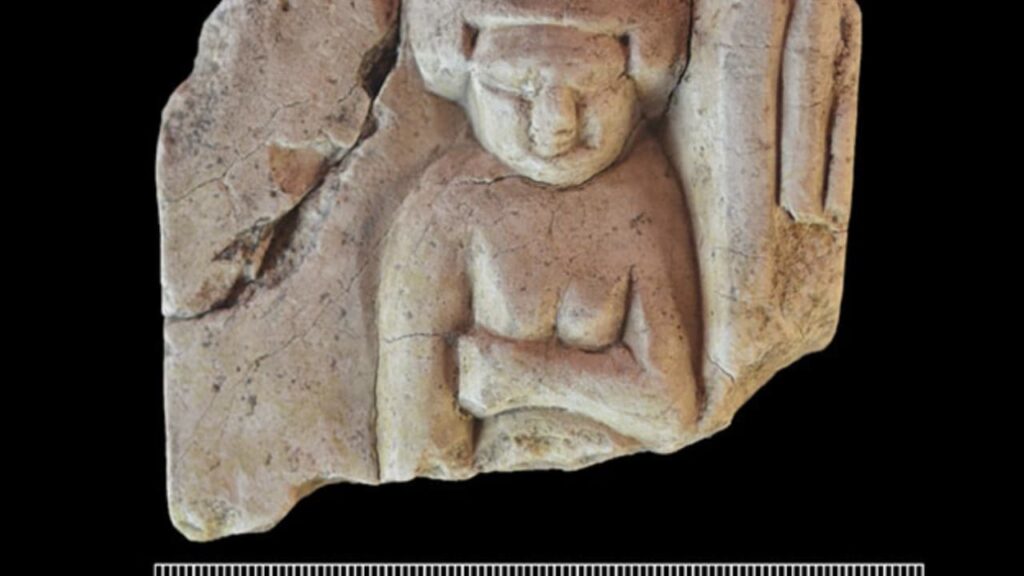

Now, hear the chisel strikes. In other rooms, archaeologists found unfinished limestone statues and artifacts in mid-creation. This was a center for stoneworking and sculpture.

See the gleam of molten metal and glazed ceramic. Evidence points to separate spaces for metalworking and the crafting of faience amulets—those iconic blue-green protective charms worn by Egyptians for millennia.

This single complex was a hive of specialized craft production. It turned local materials and Mediterranean catch into valuable goods for trade.

A Gateway to the Mediterranean World

How do we know this town was connected? The artifacts speak of far-reaching links.

Found amid the Egyptian bones and limestone were imported treasures. Fragments of Greek pottery and amphorae—the sturdy transport jars of the ancient world—dot the site. Some date as early as the 5th century BCE.

This places the site’s booming activity centuries before Cleopatra’s reign. It thrived in the Late Period of Pharaonic Egypt and continued seamlessly into the Greco-Roman era.

The geographical clue is key. Located in the western Delta, this town sat inland from the mighty port of Alexandria. It was a vital hinterland hub. Raw materials and agricultural products flowed from here to the great cosmopolitan port. In return, ideas, people, and finished goods flowed back.

This workshop wasn’t just serving a local village. It was likely feeding the insatiable demands of Alexandria itself, and by extension, the entire Mediterranean basin.

The City of Silence: Stories in Bone and Gold

Just a stone’s throw from the industrial clamor lies the necropolis. Here, the Roman-era residents entered their final rest. The variety of burials paints a profound picture of community, economy, and belief.

There was no one way to be buried. The team discovered simple pit graves cut directly into the earth. They found more elaborate burials within pottery coffins. And most poignant of all, they uncovered child burials placed gently inside large amphorae.

These “jar burials” for children are a touching tradition seen across the Roman world. The imported transport vessel becomes a protective womb for a life ended too soon.

The Bioarchaeology of Life

The skeletal remains of 23 individuals have been recovered. They are now undergoing meticulous bioarchaeological analysis. Scientists are peering into these bones to read the stories of their lives.

Early results are revealing. These were not people suffering severe deprivation or widespread violence. The bones show relatively good living conditions, with no clear signs of mass disease or traumatic injury.

This suggests a stable, functioning community supported by its thriving industries.

The Girl with the Golden Earrings

Among the silent population, one individual whispers a little louder. Archaeologists found a pair of delicate gold earrings, likely belonging to a young girl.

This single, small find is electrifying. It speaks of personal wealth, familial love, and aesthetic taste. It tells us that the prosperity generated in the workshops nearby translated into personal adornment and status. Even in death, identity and beauty were paramount.

Global Implications: Rewriting the Delta’s Narrative

Why does this matter to a global audience? Because it shatters monolithic views.

This discovery moves us beyond kings and pyramids. It forces us to look at the economic engine rooms that made grand civilizations possible. The salted fish from this Delta workshop may have ended up on a Roman soldier’s plate in Britannia. The amulets shaped here may have protected a merchant sailing to Athens.

It reveals cultural fluidity. Here, Egyptian funerary practices (like amulets) blend with Roman burial styles (like child jar burials). Local limestone statues are made alongside Greek-style pottery. This was a hybrid, cosmopolitan society, long before the modern term existed.

It redefines “provincial” life. This was no backwater. The western Nile Delta, often overshadowed by Thebes or Memphis, is now emerging as a critical, vibrant region. It was the breadbasket and workshop for the glittering world of Alexandria.

As Dr. Cristina Mondin, the mission head, emphasizes, ongoing analysis will refine our understanding of this community’s demographics and daily rhythms. Each fish bone and tool fragment is a data point in rebuilding a lost world.

What This Means for History

The Kom Al-Ahmar and Kom Wasit site is a revolutionary window. We are no longer just studying monuments. We are reconstructing livelihoods.

We see the complete cycle of ancient life. The production, the trade, the community, and its final rituals. This find proves that the arteries of the ancient world—its trade routes and economic networks—pulsed deep into the Egyptian countryside.

It underscores Egypt’s enduring role not as an isolated wonder, but as the beating, productive heart of the Mediterranean world for millennia. From the Pharaohs to the Romans, its towns and people were inextricably linked to a globalized ancient system.

5 In-Depth FAQs

1. How was this site discovered? Was it an accident?

This was no accidental find. It was the result of a sophisticated, joint mission guided by historical maps, geographical surveys, and an understanding of ancient settlement patterns. The team targeted the Beheira region specifically to investigate the often-overlooked western Delta hinterland of Alexandria, leading them to the promising mounds known as Kom Al-Ahmar and Kom Wasit.

2. What is the single most important artifact found?

While the gold earrings capture the imagination, the 9,700 fish bones are arguably the most revolutionary find. This quantitative, biological evidence proves large-scale industrial activity. It transforms the site from a generic “settlement” into a identified economic powerhouse for a specific, valuable commodity in the Roman world.

3. Why is the mix of Egyptian and Greek/Roman artifacts so significant?

This blend, or “hybridity,” shows cultural adaptation and continuity. It proves that after Alexander the Great’s conquest, Egyptian society wasn’t simply replaced. Instead, it absorbed and integrated new influences. The local population likely maintained traditional crafts (amulet making) while adopting new economic opportunities (fish sauce for Roman markets) and burial customs.

4. What can we really learn from studying human remains?

Bioarchaeology is like forensics for the ancient world. From the 23 skeletons, scientists can determine average age of death, common diseases, diet (through isotope analysis), physical stress from labor, and even familial relationships through DNA. This turns anonymous “burials” into a demographic profile of a real, living community.

5. How does this discovery change the view of Alexandria’s importance?

It elevates it further, but in a new way. Alexandria wasn’t a lonely beacon of Greek culture. It was the glittering tip of a vast regional iceberg. This discovery shows the deep, productive Egyptian hinterland that supplied and supported the cosmopolitan metropolis. Alexandria’s greatness was built on the labor and resources of towns like this one across the Delta.