In the shadow of the Margalla Hills in Pakistan lies a silent, grassy mound. For centuries, it has guarded a secret at the heart of the ancient world.

This is the Bhir Mound, the original urban core of legendary Taxila. It was a university city, a mercantile hub, and a spiritual melting pot where Zeus, Buddha, and Shiva were worshipped on the same street.

Now, archaeologists have struck a find that illuminates this forgotten era of fusion. A handful of bronze coins and a few chips of deep-blue stone are rewriting the story of one of history’s most dynamic empires. This is the story of the Kushan Empire, told not in dusty scrolls, but in metal and lapis lazuli.

THE ASTONISHING FIND: A DECADE-DEFINING DISCOVERY

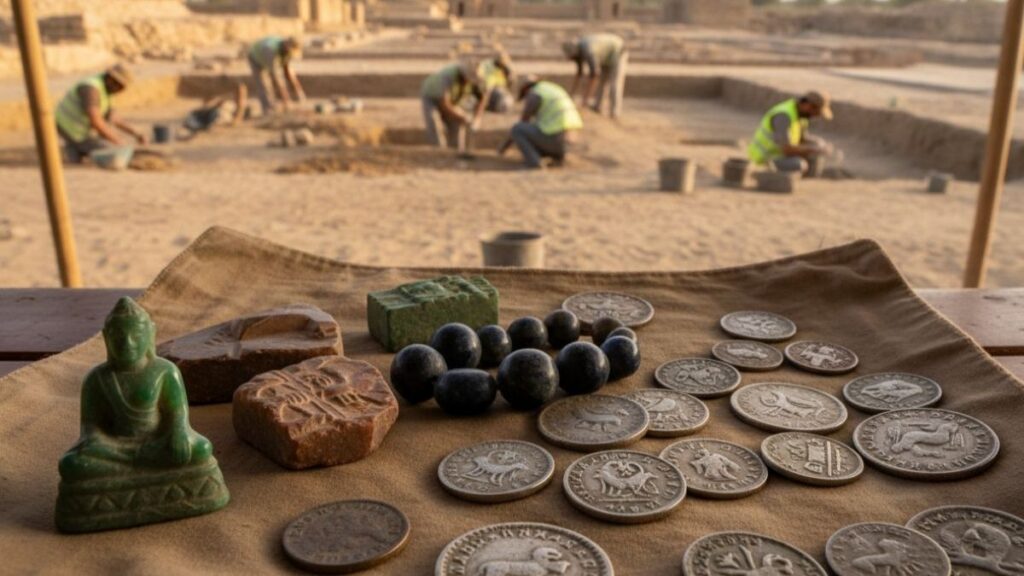

The recent excavation, hailed as the most significant at the site in ten years, was methodical and precise. Teams focused on a series of sixteen trenches, carefully peeling back layers of history.

In a trench designated B-2, on the northern residential edge of the ancient city, the soil gave up its treasures. The finds were not grand statues or golden hoards, but something far more telling: the everyday remnants of a global superpower.

The team, led by Aasim Dogar, Deputy Director of Punjab Archaeology, unearthed two distinct categories of artifacts. First, bronze coins from the 2nd century AD. Second, stunning fragments of semi-precious decorative stone dating back to the 6th century BC.

Together, they form a dual-pronged key to unlocking Taxila’s past.

WHAT THE ARTIFACTS REVEAL: THE FACE OF A SYNCRETIC EMPIRE

The Coins: Portable Propaganda of a Pluralistic Realm

The coins underwent meticulous numismatic analysis by specialists from the University of Peshawar. They were definitively attributed to the Kushan Empire, and more specifically, to Emperor Vasudeva I.

He ruled around 190-230 AD and is considered the last of the “Great Kushans.” His coins are a masterpiece of ancient political messaging.

The obverse (front) bears the emperor’s image. He is shown in the heavy, ornate Central Asian royal coat and boots of the Kushan elite—a stark declaration of his nomadic steppe heritage.

The reverse is where the story gets electrifying. It depicts a female deity. This is not an anomaly. Kushan coinage is renowned for its breathtaking religious diversity.

Across the empire’s currency, one could find Greek god Helios, Persian sun god Mithra, Hindu god Shiva, and of course, the Buddha. This was a deliberate imperial policy. By showcasing a pantheon of gods, the Kushans politically and culturally unified their incredibly diverse subjects from Central Asia to North India.

The Stones: A Blue Thread Across Continents

The other groundbreaking find was lapis lazuli. This vibrant, deep-blue metamorphic stone has been prized since antiquity for its celestial color.

These fragments date to a much earlier period—the 6th century BC. This proves Taxila’s prestige and trade connections existed centuries before the Kushans.

Lapis lazuli’s only known ancient source was the mines of Badakhshan, in modern-day Afghanistan. Its presence at Taxila maps a spectacular trade route.

The stone would have traveled from Afghan mines, through the Kushan heartland, to Taxila’s workshops. From there, it could have been sent further west to Rome or east into the Indian subcontinent.

This tiny chip of blue is physical proof of Taxila’s role as a linchpin in the proto-Silk Road.

GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS: TAXILA, THE WORLD’S FIRST GLOBAL CITY

This discovery solidifies Taxila’s status as a premier “global city” of the ancient world. Under Kushan rule, particularly Emperor Kanishka the Great, it became an unparalleled nexus.

It was an administrative capital, a hub for the flourishing Gandharan art style (a unique Greco-Buddhist fusion), and a spiritual center for Buddhism. The city attracted scholars, traders, and artists from across continents.

The coins tell us how the empire governed such diversity: through religious inclusion and powerful imagery. The lapis lazuli shows us the economic arteries that fed its prosperity.

These finds connect dots across the ancient map. They tie the steppes of Central Asia to the forums of Rome and the philosophies of India. This was a world far more interconnected than we often imagine.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR HISTORY: REDEFINING THE KUSHAN LEGACY

For decades, the Kushan Empire has been a shadowy giant in history books, often overshadowed by Rome and Han China. This discovery at Bhir Mound brings them into sharp, vivid focus.

It moves them from abstract “nomadic rulers” to sophisticated imperial administrators. They were masters of soft power, using coinage as mass media to promote a unifying identity across ethnic and religious lines.

The finds also dramatically extend Taxila’s active timeline. The 6th-century BC lapis lazuli shows its importance during the Achaemenid Persian Empire period. The 2nd-century AD coins show its zenith under the Kushans.

This continuity makes Bhir Mound a living archive of over half a millennium of urban, intellectual, and commercial history. It confirms that ideas, goods, and beliefs flowed freely here, making it a crucible for the cultural fusions that define the region to this day.

The excavation continues. Each handful of soil from this UNESCO World Heritage Site promises to further untangle the threads of our collective global past, reminding us that the forces of cultural exchange and economic connection are as old as civilization itself.

5 IN-DEPTH FAQs

1. Why is Taxila so significant in world history?

Taxila (or Takshashila) is one of the most important archaeological sites in South Asia. It was a major Vedic/Hindu and Buddhist center of learning from at least the 5th century BC. It flourished as a crossroads under the Achaemenid Persians, Alexander the Great, the Mauryans, and most spectacularly, the Kushans. It is considered a birthplace of the unique Gandharan art style.

2. Who were the Kushans, and why was their empire so unique?

The Kushans were a confederation of nomadic tribes from Central Asia who established an empire stretching from Afghanistan to North India (c. 1st-3rd centuries AD). Their uniqueness lay in their synthesis of cultures. They adopted elements of Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions, creating a remarkably pluralistic society that facilitated trade and cultural exchange along the Silk Road.

3. What is so special about finding lapis lazuli at the site?

Lapis lazuli is a tracer for ancient long-distance trade. Its sole ancient source was Afghanistan, meaning any piece found elsewhere traveled. Finding it at Taxila, dated to 600 BC, proves the city was part of extensive luxury trade networks centuries before the Silk Road’s classical peak. It turns Taxila from a regional center into a confirmed international node.

4. How do coins help archaeologists more than just dating a layer?

Coins are “primary source documents” minted by the state. Their imagery, metal content, and inscriptions reveal political ideology, economic policy, religious beliefs, and trade connections. The Vasudeva coin doesn’t just date the layer; it shows the empire’s syncretic religious policy and the ruler’s desire to project both royal and divine authority.

5. What will happen to these artifacts now?

The artifacts will be thoroughly cleaned, conserved, and studied in laboratory conditions. They will be cataloged and analyzed to extract maximum data (e.g., metallurgy of the coins, precise sourcing of the lapis). Ultimately, they will be preserved in a national museum, likely in Islamabad or at the Taxila Museum itself, where they will become part of Pakistan’s and the world’s displayed heritage.