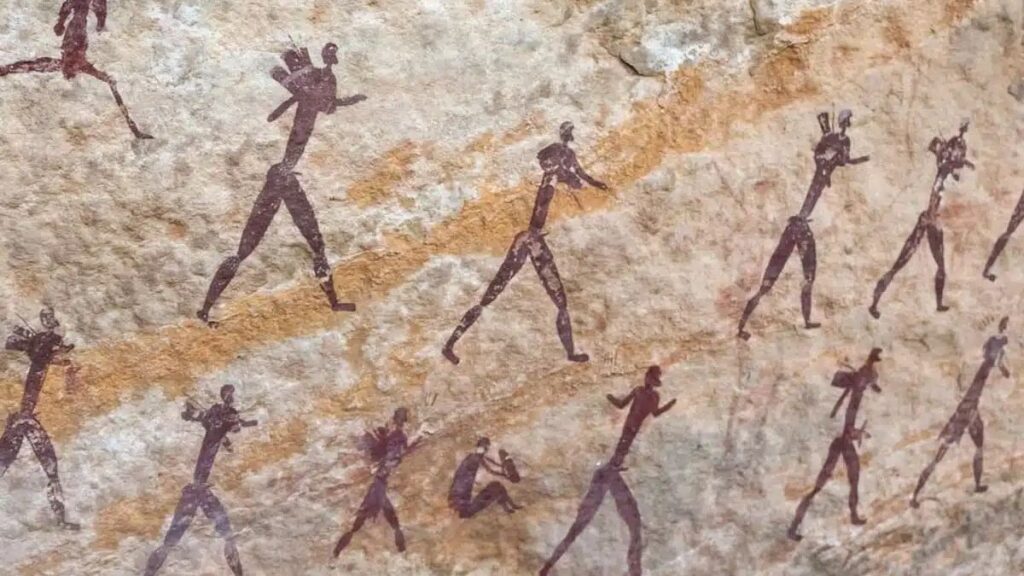

The Fossil Hunters of 1820: Imagine a skilled artist, part of the San people, painting on a sacred rock wall in South Africa’s Karoo region around the year 1825. They depict antelope, human figures, and spiritual scenes drawn from a deep connection to the living world.

And then, they paint something else. A bizarre, elongated creature with stumpy legs, a small head, and sinister, downward-curving tusks.

For nearly two centuries, this enigmatic figure has baffled everyone. It looked like a walrus stranded in a desert. It was labeled a mythical “horned serpent,” a being of pure spirit.

But what if this myth was born from a tangible, terrifying reality? What if the artist was not imagining a spirit, but recording a memory—a memory preserved in stone for 250 million years?

THE ASTONISHING FIND: THE HORNED SERPENT PANEL

The artwork in question is part of the renowned “Horned Serpent Panel.” It was created between 1821 and 1835, a precise date determined through historical analysis of depicted clothing and artifacts.

The panel is a masterpiece of San rock art, a tradition stretching back thousands of years. San art is deeply symbolic, often blending observations of nature with shamanistic visions.

But this one creature stood out as an extreme outlier. It bore no resemblance to any animal in the San’s world. The arid Karoo plains are a world away from the Arctic habitats of walruses.

This presented a profound mystery. The San are renowned naturalists. Their art is rooted in meticulous observation. So what, or what, were they observing?

WHAT THE ARTIFACTS REVEAL: FOSSILS AS FOLKLORE

Researcher Julien Benoit from the University of the Witwatersrand proposed a revolutionary theory. He looked past the living world and into the deep earth.

The key was location. The Karoo Basin is one of the planet’s richest fossil graveyards. For over 200 million years, it has preserved a near-continuous record of life.

Its rocks are littered with the bones of ancient beasts. These fossils erode out of the ground constantly, lying in full view.

Benoit asked a simple, brilliant question: If the San people encountered these strange, petrified bones, how would they interpret them? To a culture that saw the world as deeply interconnected, ancient bones would naturally become part of their cosmology.

The art wasn’t a literal portrait. It was a cultural interpretation of a tangible, yet incomprehensible, object.

THE PERMIAN PROGENITOR: ENTER THE DICYNODONT

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, pinpointed a specific prehistoric animal as the likely inspiration.

Meet the dicynodont.

This creature was a therapsid, a “mammal-like reptile” that dominated the planet long before the dinosaurs. It thrived in the late Permian period, around 250 million years ago.

Dicynodonts were stocky, barrel-bodied herbivores. They had short, powerful legs, a distinctive beaked skull, and—crucially—a pair of prominent, downward-curving tusks.

Fossils of these animals are among the most common finds in the Karoo. They are so abundant that they are considered index fossils for the period.

Side-by-side comparisons are stunning. The painting’s elongated body mirrors the fossilized skeleton. The stumpy limbs align perfectly. Most conclusively, the unique, curved tusks are a direct match.

The San artist depicted a Dicynodon skeleton, not a living animal. They painted the fossil as they saw it: a mysterious, tusked being lying in the stone.

GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS: REWRITING THE HISTORY OF PALAEONTOLOGY

This is not merely an art historical curiosity. It is a mind-blowing reframing of human intellectual history.

The official scientific description of the dicynodont occurred in 1845. Western science “discovered” it then.

But the San painting predates that by two decades. This suggests Indigenous knowledge systems encountered and cataloged this extinct species long before formal paleontology existed.

It forces us to reconsider folklore and myth worldwide. How many other “mythical” creatures—dragons, giants, thunderbirds—were inspired by the colossal bones of mammoths, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs?

The study argues that the San, and potentially other ancient cultures, were the world’s first paleontologists. They observed, collected, and sought to explain fossils, weaving them into their understanding of the world.

This bridges a gap we never knew existed. It connects the deep time of the Permian period with the very recent past of the 19th century through the medium of human storytelling.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR HISTORY: A NEW LENS ON ANCIENT KNOWLEDGE

The “Horned Serpent Panel” is now a dual treasure. It is a beautiful work of art and a profound historical document.

It shatters the arrogant notion that non-Western cultures were passive inhabitants of their landscapes. The San were active interpreters of a deep, layered environment.

This discovery elevates Indigenous knowledge systems. It shows they contain longitudinal data about geology, ecology, and paleontology that modern science is only beginning to decode.

For archaeologists and anthropologists, it provides a powerful new key. When encountering strange figures in global art, they must now ask: Could this be a fossil?

The painting reminds us that human curiosity is universal and ancient. The drive to explain the unexplainable—whether through science or story—is what makes us human.

The San artist who mixed their pigments 200 years ago did more than create myth. They left a coded message across time, a message we have only just learned to read: “We saw the bones of the old world. And we remembered.”

5 IN-DEPTH FAQs

1. How can we be sure the San saw fossils and not a living, unknown animal?

The anatomical match is too specific. The painting depicts key skeletal features of a dicynodont fossil—the elongated spine, limb placement, and tusk shape—not the fleshed-out proportions of a living creature. No known animal, living or recently extinct in Africa, matches this morphology.

2. Why wouldn’t the San have drawn other dinosaurs if they saw fossils?

Dicynodont fossils are exceptionally abundant and erode out of the ground in complete, recognizable skeletons in the Karoo. Dinosaur fossils from later periods are found there too, but often as scattered, less-identifiable fragments. The most common and visually coherent fossil would logically make the strongest cultural impression.

3. Does this mean the San understood deep time and extinction?

Not in the modern scientific sense. They would not have conceptualized 250 million years. Instead, they likely integrated these objects into their spiritual worldview, seeing them as remains of ancestral beings or creatures from a primordial “dreamtime.” This is still a form of understanding, just framed within their cosmology.

4. Are there other examples of fossils influencing ancient art?

Yes, there are growing theories. Some scholars suggest Cyclops myths originated from dwarf elephant skulls found in the Mediterranean. Native American stories of “water monsters” may be influenced by dinosaur fossils eroding from badlands. This South African case is one of the most visually compelling and well-researched examples to date.

5. What happens to the rock art site now?

The site is a protected heritage location in South Africa. This new interpretation amplifies its significance. It is now a critical piece of evidence for both San cultural heritage and the global history of science. Conservation efforts to protect the delicate pigments from weathering and vandalism are more important than ever.