Imagine a message, carved not in fleeting digital code, but into the very skin of a desert mountain. A message of conquest, broadcast 5,000 years ago. In the stark, silent expanse of southwestern Sinai, archaeologists have found precisely that: the world’s oldest known political billboard. It is not a benign record of trade, but a stark tableau of domination—a victor and his victim, frozen in stone for millennia. This isn’t just art. This is ancient Egypt announcing its power to the world, in a language of violence that needs no translation.

The Astonishing Find: A Scene Written in Stone and Blood

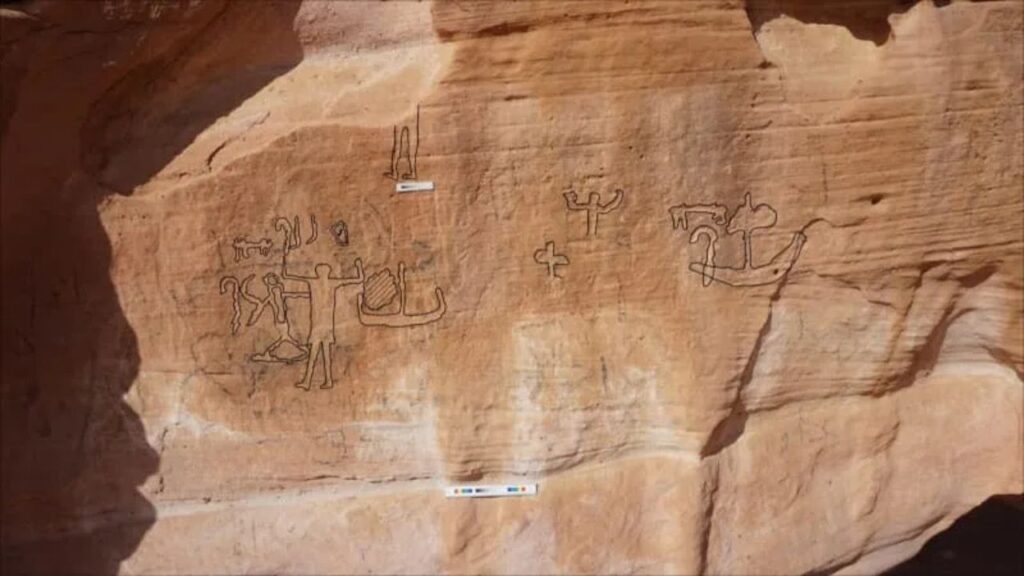

The discovery in Wadi Khamila, a parched valley far from the life-giving Nile, is revolutionary. It pushes the timeline of Egyptian imperial ambition centuries earlier than previously confirmed. The carving is brutally simple, yet its narrative is devastatingly clear.

The Oldest Story of Conquest

A towering Egyptian figure, his arms raised in a timeless victor’s pose. Before him, a local Sinaite kneels, an arrow piercing his chest. “This is one of the oldest known scenes of killing with an accompanying inscription,” explains Egyptologist Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz, who interpreted the find made by Egyptian archaeologist Mustafa Nour El-Din.

This is more than a battle record. It is a psychological weapon. Carved at a strategic desert crossroads, it was a permanent, unavoidable declaration to locals and travelers alike: Resistance is futile. This land is ours.

Deep Dive: The Colonial Network Revealed

The location is the real mind-blower. Previous finds had hinted at Egyptian activity in Sinai, often linked to mining expeditions for precious turquoise and copper. But this scene in Wadi Khamila is different. It’s not about resource extraction; it’s about territorial control and subjugation.

A Forgotten Frontier Outpost

“The southwest of the Sinai is the region in which we can find economically motivated colonization,” states Morenz. This carving is the smoking gun. It suggests Egypt wasn’t just sending mining parties, but establishing a “colonial network”—a systematic, militarized presence to secure its interests and intimidate the indigenous population. This transforms our understanding of the early Egyptian state from a Nile-centric kingdom into a nascent empire projecting power hundreds of kilometers from its core.

The Mysterious Vandalism: A Name Erased from History

Adding a layer of profound mystery, the researchers found more than just violence. A carving of a boat was discovered nearby. And next to it, the ghost of a name.

A Pharaoh’s Memory, Deliberately Scratched Out

The study in Blätter Abraham reveals a stunning detail: the space where a pharaoh’s name was once carved shows clear signs of deliberate erasure. Who did this? And why? Was it an act of rebellion by the subjugated locals, scratching out the name of their oppressor centuries later? Or was it internal Egyptian politics—a later pharaoh chiseling away the legacy of a predecessor? This silent act of vandalism is a 5,000-year-old crime scene, whispering of power struggles lost to time.

Divine Sanction: The God of the Frontier

The narrative carved into this landscape didn’t stop with human actors. Nearby, an inscription invokes the Egyptian deity Min, explicitly described as the “divine protector of the Egyptians in areas beyond the Nile Valley.” A second depiction of Min was later discovered by El-Din.

The Theology of Empire

This is crucial. The Egyptians weren’t just claiming land; they were sanctifying their conquest. By invoking Min—a god of fertility, but also of desert routes and travelers—they were weaving their colonial project into a divine mandate. It was a message to their own people and to the gods: Our presence here is not just strategic; it is holy and protected.

What This Means for History: Rewriting the Dawn of Empire

This discovery shatters the quiet image of early dynastic Egypt. We are now looking at a state with the administrative will, military capability, and ideological drive to enforce its rule in distant, hostile territories over five millennia ago.

The Birth of Propaganda: This is arguably the oldest clear example of state-sponsored propaganda, using public art to cement a narrative of invincibility.

A Colonial Blueprint: It proves that the mechanisms of empire—military domination, ideological justification, and strategic messaging—were in place far earlier than historians believed.

An Archive in the Open Air: As El-Din and Morenz assert, this is just the beginning. “Research has just begun,” they say, planning a larger campaign. Wadi Khamila is likely an open-air archive, holding more stories of conquest, trade, and daily life on history’s first imperial frontier.

The Silent Stones Speak

The desert of Sinai, long considered a peripheral landscape, has now stepped onto the center stage of ancient history. These carvings are a brutal, beautiful, and complex testament to humanity’s age-old drives: the hunger for resources, the will to dominate, the need to justify, and the enduring desire to leave a mark that says, We were here, and we were powerful. The stones of Wadi Khamila are no longer silent. They are screaming a 5,000-year-old story of empire’s first, unforgiving breath.