For decades, the story of the first Americans was a relatively simple textbook chapter: the Clovis people, with their distinctive stone spear points, crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia around 13,000 years ago, becoming the continent’s pioneering settlers. This “Clovis First” model dominated archaeology for most of the 20th century. But a groundbreaking discovery in the remote Alaskan wilderness has now provided the most robust “missing link” in this epic migration story, pushing definitive evidence of human presence back by a millennium and directly connecting Siberian ancestors to the famed Clovis culture.

The Discovery: A 14,000-Year-Old Workshop in the Tanana Valley

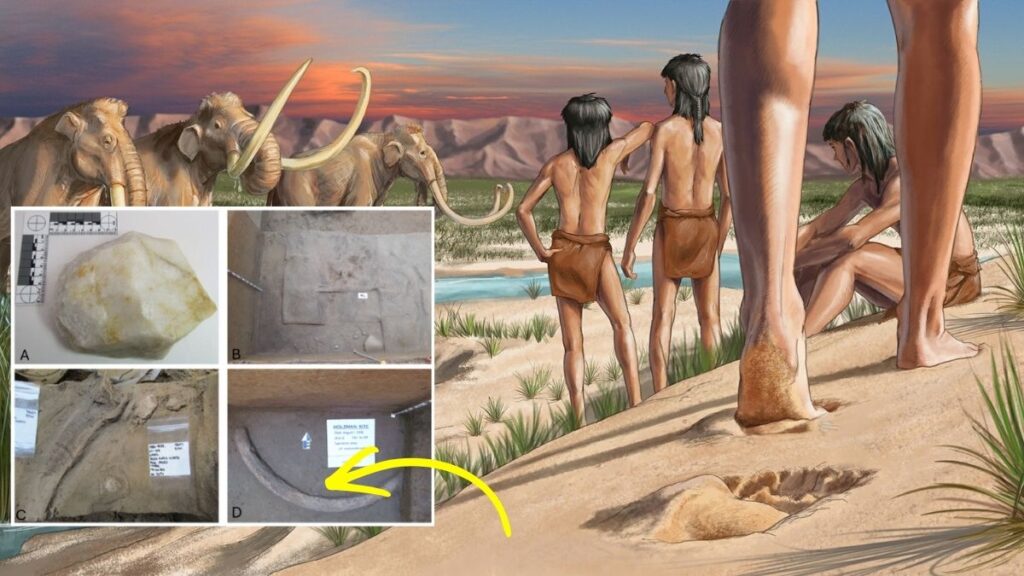

At the Holzman archaeological site in Alaska’s middle Tanana Valley, a research team led by Brian Wygal of Adelphi University unearthed evidence that has dramatically refined the timeline of human arrival in the Americas. Within a 14,000-year-old layer of earth, they found not just stone tools, but something far more distinctive and telling: human-made tools crafted from mammoth ivory.

Key Artifacts from the Holzman Site:

Mammoth Ivory ToolkitStone ToolsFemale Mammoth TuskWorkshop Evidence workshop

Artifact TypeWhat Was FoundSignificance Ivory rods, blanks, and production fragments.Ivory working is a signature technology linking Siberia to Clovis culture. These are the oldest such tools found in the Americas. Quartz bifacial choppers, scrapers, hammerstones, and flakes.Shows a diverse toolkit for processing animals, plants, and ivory. The quartz source indicates resource knowledge. A nearly intact tusk, cached near a small hearth.Provides direct evidence of human interaction with Ice Age megafauna, likely for raw material and possibly food. Concentrated area with ivory fragments, tools, and a hearth.Indicates this was not a temporary camp, but a site for sustained, specialized activity—a .

The radiocarbon dating of this layer to 14,000 years ago is pivotal. It places humans in interior Alaska 1,000 years before the classic Clovis culture flourished in the continental United States. The tools, especially the ivory rods, are technological precursors to later Clovis artifacts, creating a clear cultural lineage.

Solving the Migration Puzzle: From Beringia to the Great Plains

This discovery acts as a crucial piece in the complex puzzle of how and when humans populated the Americas. It supports a refined model of migration:

- The Beringian Stage: During the last Ice Age, lower sea levels exposed the Bering Land Bridge, creating a vast subcontinent called Beringia that connected Siberia and Alaska. Genetic and archaeological evidence shows people lived in this shrub-tundra region for millennia.

- The Alaskan Haven: As ice sheets covered much of Canada, movement south was blocked. The newly discovered site suggests groups moved into ice-free refugia like the Tanana Valley. Here, they hunted local megafauna (like the woolly mammoth) and developed their distinctive toolkit.

- The Southern Dispersal: Around 13,500 years ago, an ice-free corridor opened between the retreating Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets. The descendants of these “First Alaskans,” carrying their ivory- and stone-working knowledge, traveled this corridor south. Within centuries, their technology evolved into the full-blown Clovis culture that spread across North America.

This model elegantly connects the dots: Siberian progenitors → Beringian inhabitants → First Alaskans (at sites like Holzman) → Clovis pioneers.

Weighing the Evidence: Why This Site is a Game-Changer

In the often contentious debate about the “First Americans,” the Holzman site evidence stands out for its clarity and solidity.

- Compared to Other Early Sites: Other claims of pre-Clovis settlement, like the White Sands footprints (~23,000 years old), are revolutionary but subject to ongoing debate about dating methods. The coastal kelp highway theory is compelling but hard to prove, as most ancient coastal sites are now deep underwater. The Alaskan site’s strength lies in its unambiguous stone and ivory tools found in a clearly dated geological layer with evidence of sustained human activity.

- The Ivory Connection: The use of mammoth ivory is a technological “smoking gun.” This specialized practice was a hallmark of Upper Paleolithic groups in Siberia and, later, the Clovis culture. Finding 14,000-year-old ivory tools in Alaska provides a direct technological link across time and space, strongly supporting a migration of people and their ideas.

The Bigger Picture: Rethinking Human Resilience and Adaptation

Beyond rewriting timelines, the Tanana Valley discovery offers a profound look at human capability.

- Mastery of a Harsh Environment: Thriving in interior Alaska 14,000 years ago required incredible resilience and adaptive skill. These were not just passing hunters; they were seasoned specialists who planned mammoth tusk caches, maintained workshops, and made calculated use of local quartz.

- Cultural Continuity Over Millennia: The site shows that the cultural seeds of what would become the Clovis culture were nurtured in the Arctic for over a thousand years before spreading south. This underscores that major technological traditions evolve over long periods in specific environments.

- A Dynamic, Multi-Stage Peopling: The “First Americans” narrative is shifting from a single, rapid event to a longer, multi-wave process. The Holzman people likely represent one key wave—the one that would eventually give rise to the widespread Clovis culture—while acknowledging that other, earlier migrations (like those suggested by White Sands) may have also occurred.

Conclusion: A Foundational Chapter Rediscovered

The ivory tools of the Tanana Valley are more than ancient artifacts; they are a foundational chapter of human history rediscovered. They provide the most concrete evidence yet for the Alaskan origins of the Clovis culture, anchoring a major strand of the American story firmly in the Arctic.

This discovery reminds us that history is not static. It is a story continually refined by the spade and the trowel. The “First Alaskans” of the Holzman site were innovators and survivors, whose adaptation to the edge of the Ice Age world ultimately paved the way for the peopling of an entire continent. Their story, preserved in fragments of stone and ivory, finally takes its rightful place at the very beginning of the American epic.